Syrian comic book writer Hamid Sulaiman says that there are two questions that he is always asked and that he still has a hard time answering.

The first is what he does for a living. Usually he goes with “graphic novelist” or “painter”.

The second is where he lives. “I have two homes,” he says, “and I don’t sleep in any of them half of the time.”

The answers reflect Sulaiman’s duality. Born in Damascus in 1986, he was forced to flee Syria in 2011, a few months after the outbreak of the civil war. After crossing Egypt and then arriving in Paris, he now divides his life between Berlin and Angouleme, the French city venerated for its comic book culture.

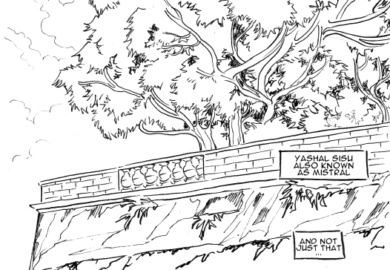

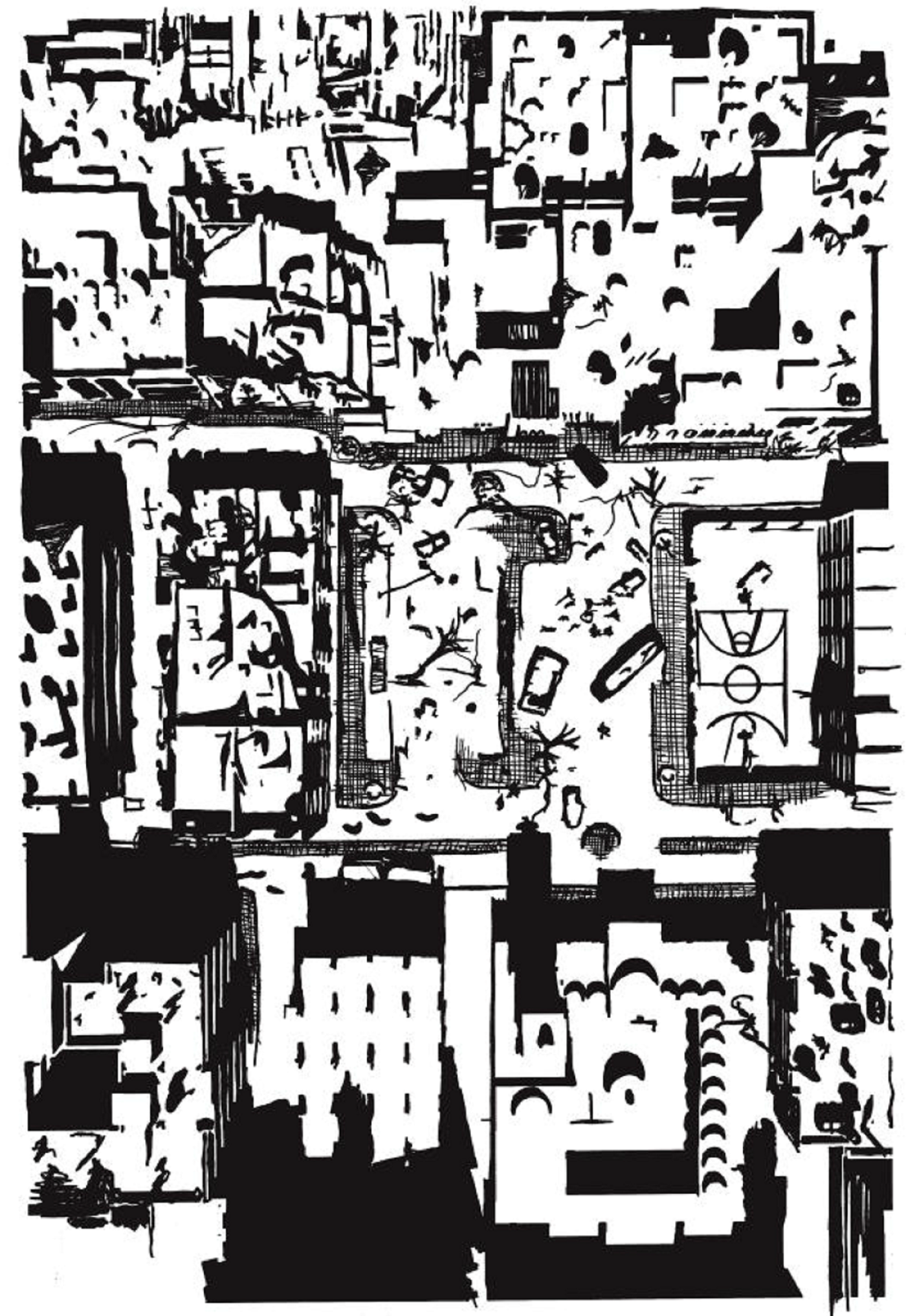

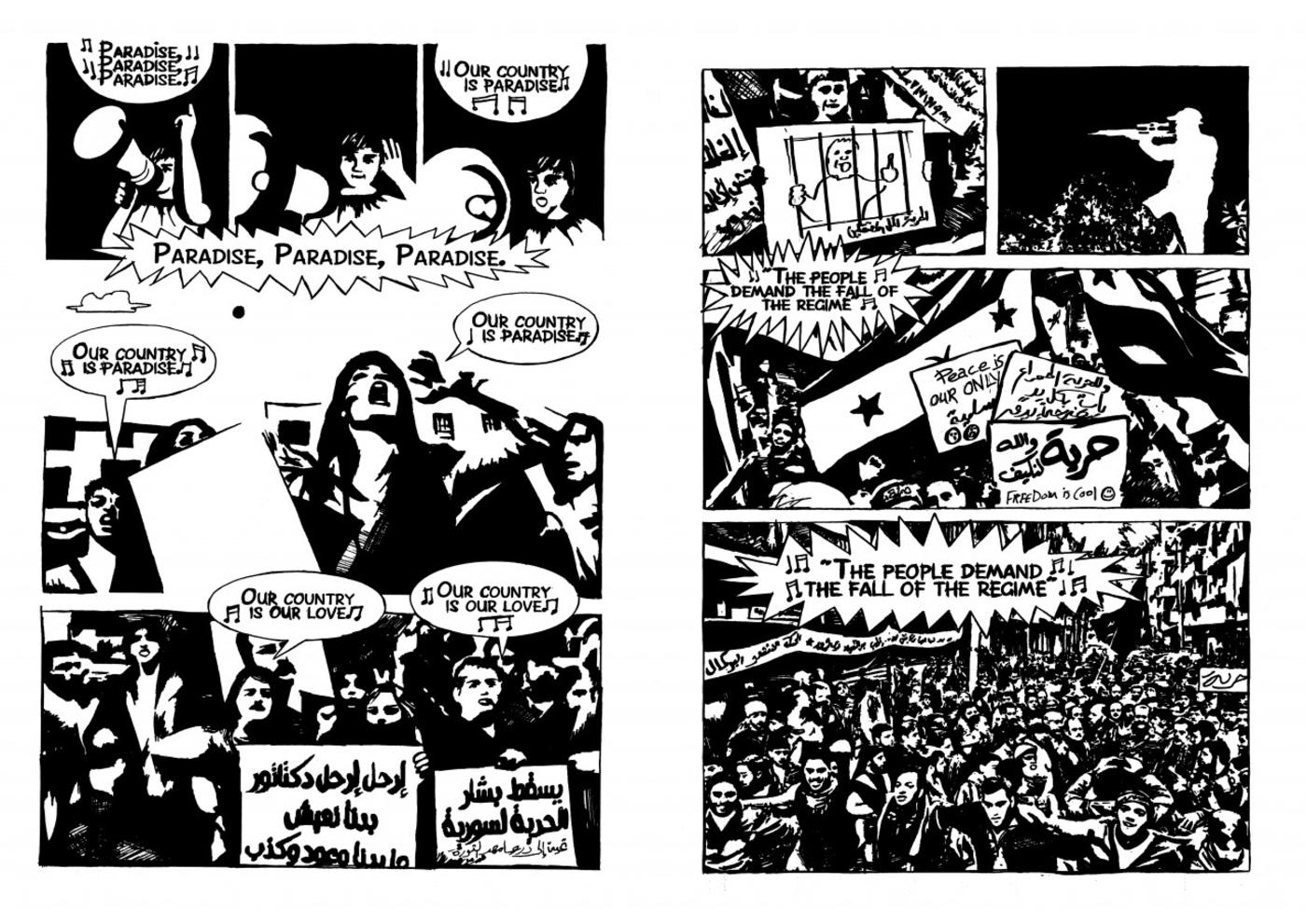

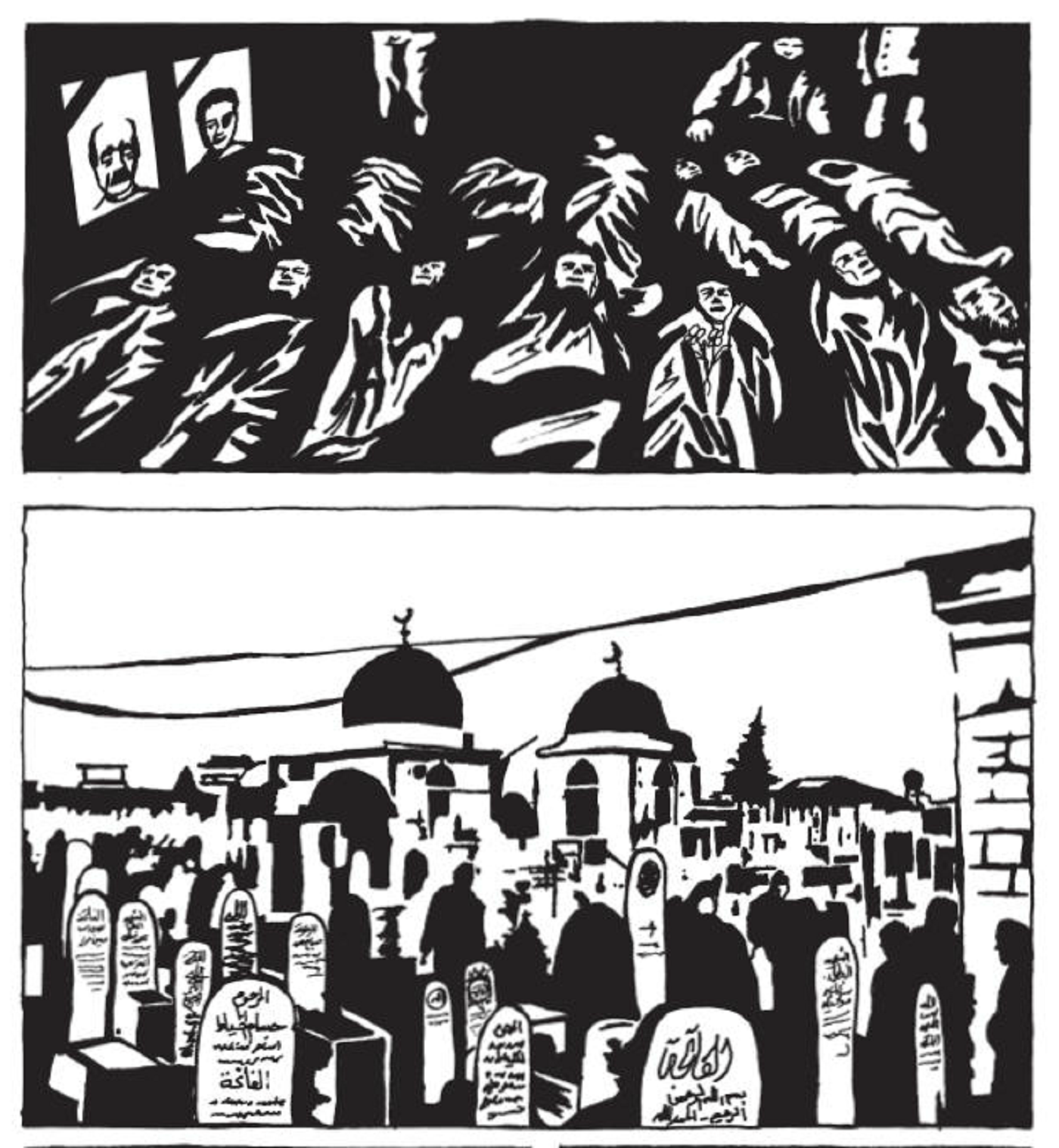

Adapting to a new life, he shared his experience, as well as those of his friends who were left in Syria, through comics. Freedom Hospital, published in 2016, soon jump-started his career. In a black-and-white, almost bleached, style it traces events at a medical centre in a fictional Syrian city, along with its cast of medics and journalists, rebels and government forces.

Translated into English, Italian, French and German, Freedom Hospital soon won the English Pen Award and a Burgess Grant. Sulaiman’s work was exhibited and collected by the British Museum among others.

Not bad for a debut novel.

Learning from legends

Sulaiman admits he possessed a certain naivete when he was working on Freedom Hospital – but he now regards it as a gift, as part of an invaluable learning experience.

“Freedom Hospital was a big, ambitious project. I lacked awareness of what it takes to make such a big work. I put all the effort into it, without having any guarantee it will even get published.”

In Syria, Sulaiman says, comics are regarded as neither art nor literature – but growing up he was willing to explore uncharted territory.

“My dream when I was young was actually working in animation,” he says. “But in Syria we didn’t have an animation university, and I couldn’t go abroad to study it. I decided to study architecture instead. In the meantime I became more and more interested in learning the comics language.”

Sulaiman’s style is not unique: look at, for example, Frank Miller’s chiaroscuro noir Sin City or Frans Masreel‘s black-and-white woodcuts from a century ago and the influences are there. Rather, Sulaiman is notable for how he re-contextualizes the styles he references, to a startling effect.

There is a sense of surprise at such an approach being applied to the Syrian conflict: the splatter of the ultra-violent Sin City, we know, belongs to the imagination. Conversely, the deaths described by Sulaiman correspond to a daily reality – and this realisation is a punch in the guts for the reader.

Sulaiman explains: “To develop my voice and my visual style, I was copying artworks from different artists, from Miller to Craig Thompson. You know what they say: if you steal from one artist you are a thief, if you steal from 10 artists you are creative.”

He laughs. “My approach to learning was very visual, and style is something I’m still developing.”

Sulaiman is aware that, since Freedom Hospital, his work has catered to an audience who are mostly interested in geopolitics and who would not automatically pick up a comic book.

Freedom Hospital, he says, ended up showing one side of the Syrian war – but it wasn’t his primary aim.

“I’m aware that, since Freedom Hospital, my work has catered to a certain audience who are mostly interested in geopolitical matters. But as an artist I’d also like to talk about other aspects of my life, my passion for art, for ink and tattoos, for life, for the cities I’ve lived in.

“I just want to make art, that’s all. My mission really comes down to drawing, writing, illustrating, telling stories. And this is the thing that I always wanted to do, and I will continue to do, no matter what.”

Since the publication of Freedom Hospital, Sulaiman has explored still further the creative process.

He refuses to dwell on the trauma of war and his forced exile, or categorise himself as simply “disapora”; rather, he has reinvented himself, plunging into his newfound passion for the world of graphic novels. In the process he found a place in his new life.

For example, it is from reading comic books, from attending lectures and from pitching projects that Sulaiman learned French (in France, comic books have traditionally had higher status than the US or UK ands are sometimes referred to as the “ninth art”).

“I didn’t miss a comic book event I could go to,” he says of those early days. “I wanted to penetrate the scene, I wanted to find an editor, I wanted to see how this will work out. This is why I was going to all the events, this was also the way to integrate for me.”

When Freedom Hospital came out, Hamid was regarded by the media as a symbol of Syrians who fled the conflict. Soon, he was being approached, almost as a representative, for geopolitical commentary pieces about the war. “Which I am not,” he clarifies. “Freedom Hospital came out from the need to re-elaborate my life experience.”

Hama 1982: Never forget

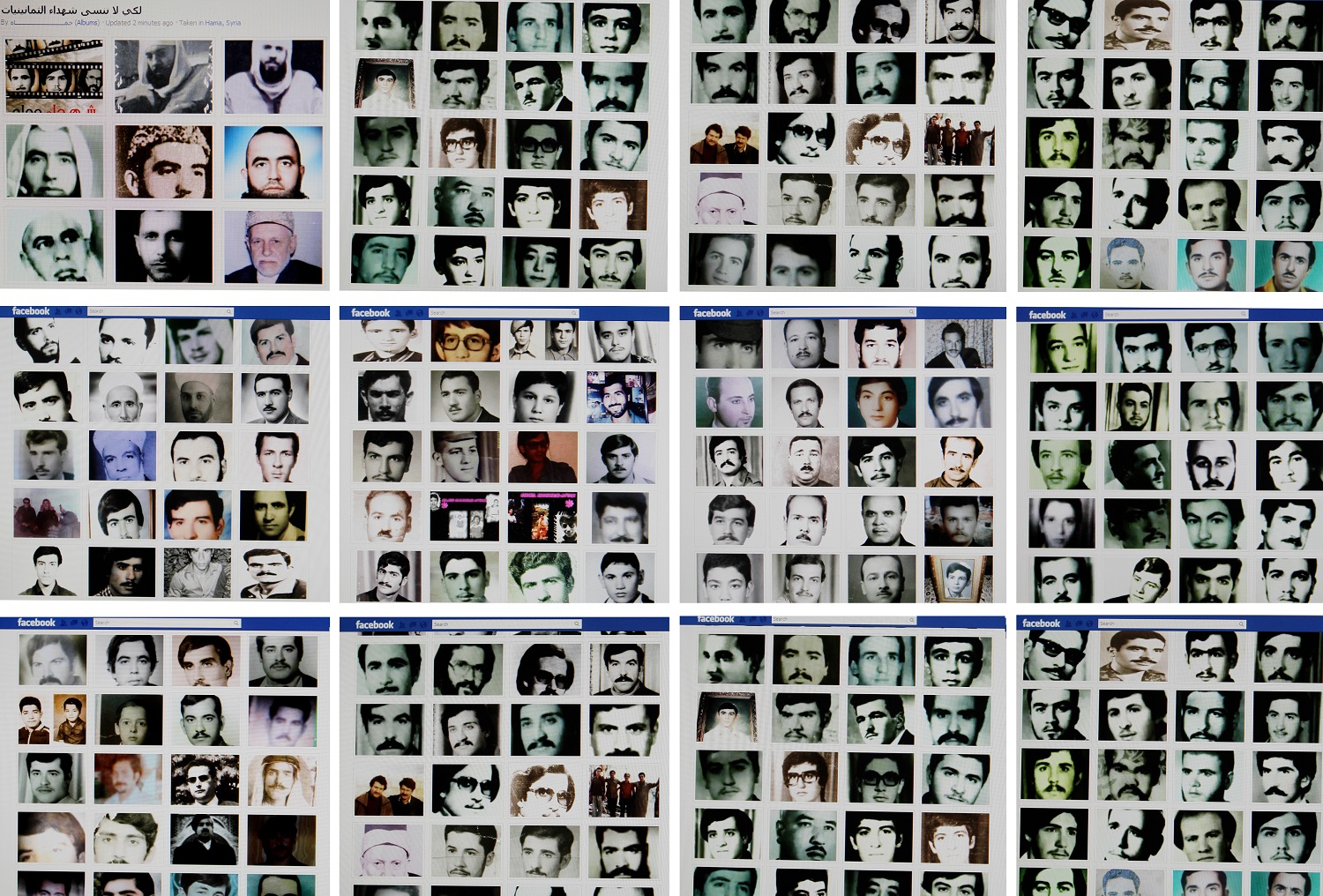

But it did spur him on to research further the modern history of Syria. He became especially interested in the massacre in Hama in February 1982, when government forces loyal to Hafez al-Assad, father of the current leader, suppressed an uprising, leaving thousands dead and the city devastated.

Sulaiman’s father worked in the area at the time as a government engineer and was told to leave the city one day before the atrocity.

“I am presenting a story that deserves to be told,” he says. “This story means so much in my personal life. I knew victims, and people who lived through the massacre.

“Still today we didn’t know how many people died,” says Sulaiman, “10,000 or 20,000 or 30,000. And there are many more who just disappeared, who went in jail and were executed there. It mirrors what is happening today.”

Sulaiman began his project in 2017, but the amount of research it has required is greater than he intitially anticipated. He has interviewed historians and academics, trying to understand more about an episode of Syrian history which has never been fully documented. He is only too aware of the importance of how he presents what happened.

“It’s a big responsibility, it’s different from Freedom Hospital which had a personal element. I had to take a different approach to this project, which I’m still developing.”

He hopes to finish in the next two years: a show is pencilled in for the 40th anniversary of the massacre at the Musee National de la Resistance in Luxembourg in February 2022.

The draw of the ink

Sulaiman is aware of his Middle Eastern heritage, and name-checks authors like Nobel Prize winner Naguib Mahfouz as key influences.

But he is also trying to make the best of his new life. In Berlin, he has become part of the tattoo community. As with graphic novels, his interest has helped him integrate and learn language skills.

The passion has been used as the basis for another comics project he is working on with the working title Fill-IN. It will tell of Sulaiman’s journey into the world of tattoos, their history and social meaning. He will also explain how he developed his own skills at and knowledge of tattooing as an extension of his existing art.

“As an artist I’d also like to talk about other aspects of my life, my passion for art, for ink and tattoos, for life, for the cities I’ve lived in,” he says.

“In comics I work with black ink, and I have been fascinated by it all my life,” he says. “My father used to be an architect and he used to draw all of his planning with black ink.”

He developed the project in March 2019 during an artist residency at Faber Residency in Spain. Sharing his creative space with fellow Syrian author Rasha Abbas, he took part in a series of discussions on the topic of “creating in exile” at the Kosmopolis Festival in Barcelona. “I tried to explain that exile is not only geographical, it’s also a state of mind,” he says.

Back when he was in Syria, he felt somehow exiled in his own country; he wanted to work with comics, something people didn’t even recognize as existing. “Now that I am exiled geographically, I long for home. Yet I’m more grateful than ever to have the opportunity to do this work.”